It’s important to remember that the term “space opera” was first devised as an insult.

This term, dropped into the lexicon by fan writer Wilson Tucker, initially appeared in the fanzine Le Zombie in 1941. It was meant to invoke the recently coined term “soap opera” (which then applied to radio dramas), a derogatory way of referring to a bombastic adventure tale with spaceships and ray guns. Since then, the definition of space opera has been renewed and expanded, gone through eras of disdain and revival, and the umbrella term covers a large portion of the science fiction available to the public. It’s critical opposite is usually cited as “hard science fiction,” denoting a story in which science and mathematics are carefully considered in the creation of the premise, leading to a tale that might contain more plausible elements.

This had led some critics to posit that space opera is simply “fantasy in space.” But it isn’t (is it?), and attempting to make the distinction is a pretty fascinating exercise when all is said and done.

Of course, if you are the sort of person who terms anything with a fantastic element as fantasy, then sure—space opera falls into that sector. So does horror and magical realism and most children’s books and any other number of sub-genres. The answer as to how much any given qualifier for a sub-genre truly “matters” is always up for debate; pairing it all down until your favorite stories are nothing but sets of rules is a tasking journey that no mortal deserves to suffer through. What does it matter, right? We like the stories that we like. I prefer adventurous stories with robots and spaceships and aliens, and nothing else will ever be as good to me. I enjoy the occasional elf, and I love magic, and fighting against a world-ending villain can be great sometimes. I also adore it when real-world science is applied lovingly to a fictional framework. But if I don’t get my lasers and my robots and poorly considered space wardrobes in regular doses, the world will not turn properly.

Which means that something about the genre is distinct—so what is it? Highlighting the variations can make a heaping difference in helping people explain what they enjoy in fiction, and to that end, the definition of space opera has had quite a journey in the popular lexicon.

To start, a word from The Space Opera Renaissance, written by David Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer. Their book defines the genre as “colorful, dramatic, large-scale science fiction adventure, competently and sometimes beautifully written, usually focused on a sympathetic, heroic central character and plot action, and usually set in the relatively distant future, and in space or on other worlds, characteristically optimistic in tone. It often deals with war, piracy, military virtues, and very large-scale action, large stakes.”

Plenty of those ideas apply in a wide spread of fantasy tales, particularly epic fantasy; central hero, war and military virtues, colorful and dramatic yarns, large-scale action and stakes. The trappings are still different in space opera, with stories set in the far future, and the use of space travel and so forth. But what about that optimism? It’s an interesting stand out, as is the tendency toward an adventure narrative. Epic fantasy can end happily and be adventurous at times, but it often doesn’t read with a plethora of either of those traits. The Lord of the Rings is harrowing. A Song of Ice and Fire is full of trauma and darkness. The Wheel of Time turns on minute detail and precise depictions of a world that has been thought through in every aspect. Fantasy lends itself to extreme specificity and worlds in turmoil—space opera doesn’t have to in order to work.

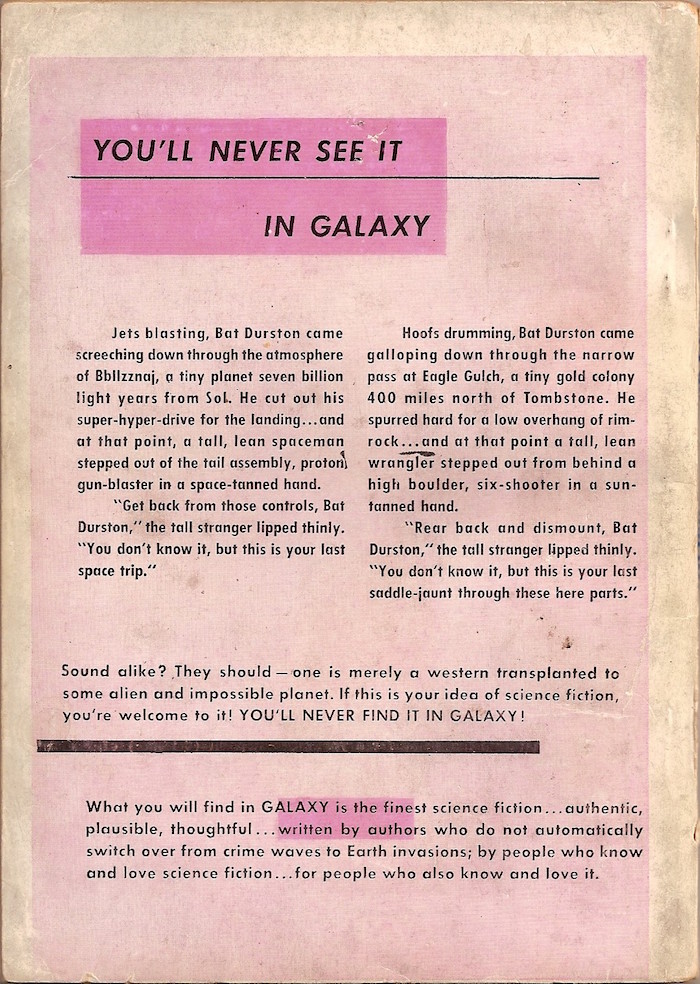

What’s more fascinating is that the comparison to fantasy is relatively new in the history of space opera’s existence as a genre. In fact, what it used to be compared to was the “horse opera”… that is, Westerns. Here is the back cover of the first issue of Galaxy Science Fiction from 1950:

Whoa. Outside the fact that this copy is throwing some serious shade, we can glean a better sense of what space opera meant to many seven decades ago, and how it was viewed. And what it reveals is perhaps a larger problem: why has space opera always been compared to other genres throughout its history? Why can’t it just be considered its own thing?

The macrocosm answer is simple enough: stories are stories. They all rely on similar devices, tropes, and narrative styles. There is very little that sets one genre apart from another in the broadest sense, and that’s perfectly fine. The microcosm answer is more complex: space opera used to be an insult, and it has taken years and the advent of incredibly successful space operas—like Star Wars and the Vorkosigan Saga and the Culture series—to allow it to stand on its own. But perhaps all those years of hanging out in the shadows has made fans more hesitant in parsing out what they love about the genre.

So what is it?

As a fan of the genre, I find the Western comparison hilarious because Westerns are very much not my thing. So what makes the difference? Why are aliens and robots important? Why are ray guns and space travel better than horses and six-shooters? There’s a part of me that wants to argue for introspection in that vein; robots and aliens are often used as a way to examine aspects of human nature, to dissect ourselves by using other beings as a template. Dwarves and orcs can do this too, but seem a bit more earth-bound, whereas robots and aliens are a part of our future—they ask questions about where we might go, what challenges we might face as we evolve.

But there’s also the “opera” part of space opera, something that doesn’t get enough credit in the phrase. After all, labeling something an opera creates a very specific expectation in the mind of your audience. It grants your story scale, yes, but not just in terms of set pieces and costumes. Opera is all about performance, about emotion. Operatic stories are bursting with feelings that can only be spelled out in all-caps. You don’t need a translation of an opera to understand it because the spectacle of it should transcend the need. Opera works with visuals, music, dance, poetry, as many forms of art as we can shove into a collective space and time. Opera is bigger than all of us.

Space operas often deliver on those terms. They are writ large and bursting with color and light. Perhaps that is the distinction worth making in the quest to explain its pull as a genre. Taking the opera out of space opera leaves us with… space. Which is great! But I don’t want to spend most of my musings on space marveling at the use of silence in Gravity. Space needs a little melodrama. It needs an opera.

Is space opera just fantasy in space? To each their own on that definition. But there’s a difference between the two all the same, and even if we don’t need to pin it down, we can at least honor the fact that space opera is no longer an insult—it encompasses many of the stories that we treasure.

Emmet Asher-Perrin has been asking for a robot friend and an alien friend since childhood. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.